The three points of view in classic fiction

A look at two core POVs with examples from intrusive and not-so-intrusive authors

When we write fiction, we must choose our story’s point of view (POV) from a menu of options, such as this:

First-person central (Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë)

First-person peripheral (The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald)

First-person unreliable (The Good Soldier by Ford Madox Ford)

Second person (“The Haunted Mind” by Nathaniel Hawthorne)

Third-person limited (The Portrait of a Lady by Henry James)

Third-person objective ("The Killers" by Ernest Hemingway)

Third-person multiple (The Wings of the Dove by Henry James)

Omniscient (Bleak House by Charles Dickens)

This can be dizzying. But really, all these options boil down to three core choices:

First-person narration: the author, like an actor, inhabits the role of a character – convincing us that there is no author-actor, only the character. That character may be focused on casting themselves as the hero of the story or they see someone else as the hero.

Second-person narration: the author addresses the reader directly, positioning the reader as the character experiencing the story.

Third-person narration: the author oversees the story, as if looking into a doll-house they built, and by describing the dolls’ actions and reading their minds, the author convinces us that the toys are alive in a real-world house. The author chooses how much to “intrude” on the narrative to make themselves known to the reader.

Fundamentally, fiction is this: an author tries to create a character experience on the page that readers can experience for themselves. POV is an important factor in how the author creates that experience.

So let’s look at POV. Second-person is rare, and I won’t delve into it today. But I’ll look at the two other basic modes of POV, starting with first person.

In which the author is an actor

In first person narratives, we usually get the direct retelling of the viewpoint character’s experience. Here’s an extract from Agnes Grey by Anne Brontë (which I’m reading right now), in which the viewpoint character is also the narrator:

Of six children, my sister Mary and myself were the only two that survived the perils of infancy and early childhood. I, being the younger by five or six years, was always regarded as the child, and the pet of the family: father, mother, and sister, all combined to spoil me—not by foolish indulgence, to render me fractious and ungovernable, but by ceaseless kindness, to make me too helpless and dependent—too unfit for buffeting with the cares and turmoils of life.

We’re “listening” to Agnes tell her story. Which means she can share her thoughts with us.

But, in reality, there is no Agnes. We’re listening to Anne Brontë pretend to be Agnes. She inhabits the role of Agnes, like an actor, and as when we attend a good play or watch a good film, we forget completely that Anne is playing a part. We believe Agnes and her direct experience.

First-person POV provides strict limitations for the writer: you’ve got to stick with that one character’s viewpoint. Within that limitation, however, you’ve got a lot of room for creativity.

Unlike Agnes above, the narrator in The Great Gatsby, Nick Carraway, focuses his attention on Gatsby, not himself. Meanwhile, the narrator in The Good Soldier by Ford Maddox Ford may not be reliable. So, as a writer of a first-person narrative, you’ll want to ask yourself:

Who is the narrator, and as the author, how am I going to inhabit this role?

Is the narrator also the central character in the story – or which other character is the narrator focused on?

How objective or reliable is the narrator – is there a gap between what happens and what the narrator reports to the reader?

Now let’s look at the third-person POV…

How the all-powerful author chooses to be visible or invisible

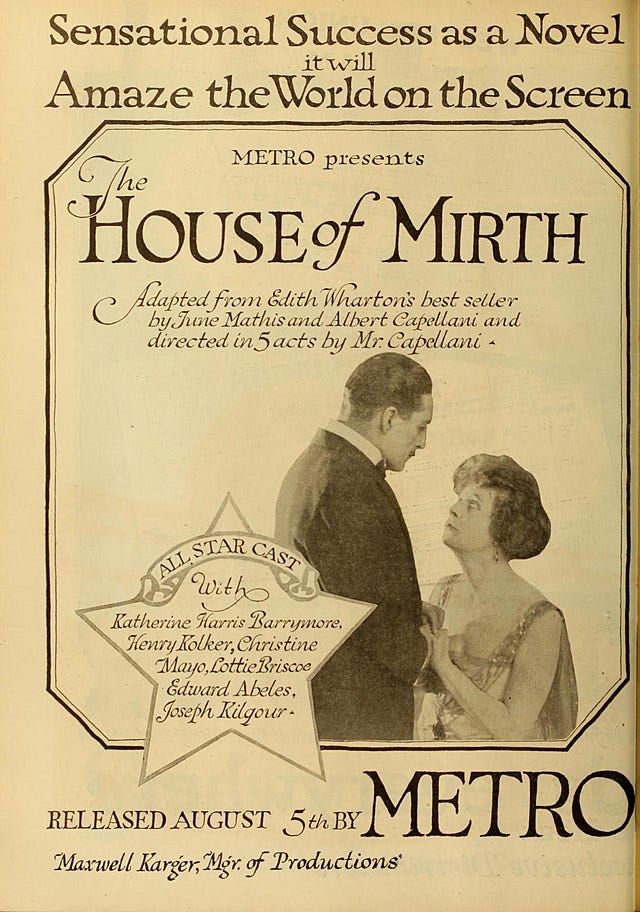

Here’s a passage from Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth:

In the hansom she leaned back with a sigh. Why must a girl pay so dearly for her least escape from routine? Why could one never do a natural thing without having to screen it behind a structure of artifice? She had yielded to a passing impulse in going to Lawrence Selden’s rooms, and it was so seldom that she could allow herself the luxury of an impulse! This one, at any rate, was going to cost her rather more than she could afford.

Here we get another viewpoint character’s experience, but in the third person (she). As in Agnes Grey, we get access to the viewpoint character’s thoughts. But who are we “listening” to now? It’s not Lily, the viewpoint character. She’s sitting alone in a hansom (a horse-drawn carriage), so there’s no one else to witness this moment. And even if she had a companion nearby, that person wouldn’t be able to read her thoughts.

So who is the narrator?

The answer, I believe, is the most obvious one: the narrator is the author, Edith Wharton. But she makes herself so unobtrusive in this passage that we forget she’s there. Only a narrow distance stands between us and Lily’s experience. That distance remains present in the word choice, most notably “she” and “her.”

Just compare the passage above with my rewriting in first person:

In the hansom I leaned back with a sigh. Why must a girl pay so dearly for her least escape from routine? Why could I never do a natural thing without having to screen it behind a structure of artifice? I had yielded to a passing impulse in going to Lawrence Selden’s rooms, and it was so seldom that I could allow myself the luxury of an impulse! This one, at any rate, was going to cost me rather more than I could afford.

One way the author hides herself is by setting strict limitations on her reach in the story world. Technically, she could jump from Lily to the hansom cab driver, up over the rooftops of the city, and then back again. But it wouldn’t serve the story – plus it would increase the likelihood that we notice the jumping, and that would draw attention to the unseen storyteller.

Too much moving around is called “head hopping,” and it’s a common mistake in first drafts, where the third-person POV slips from one character to another and then back again. It can confuse the reader. It can also draw attention away from the viewpoint character’s experience, making us aware that the author is rummaging around in the doll house.

When an author limits her movements and that limitation is applied consistently, it’s often called “third-person limited.” The passage from The House of Mirth above is consistent. We might call it “third-person limited.”

But Edith Wharton isn’t consistent throughout her book.

Meet the author

Later in The House of Mirth, Edith Wharton speaks more directly to us:

Mr. Rosedale, it will be seen, was thus far not a factor to be feared.

The “it will be seen” isn’t something Lily thinks, nor is it a thought Mr. Rosedale has. In fact, it’s a reference to the unfolding of the story itself – something only the author would know. It’s what many would call “omniscient” narration.

Mostly, Edith Wharton avoids this kind of “authorial intrusion”; her style of writing heralds the 20th century love affair with the entirely invisible narrator. In other words, a strictly controlled “third-person limited” approach to storytelling. But as E.M. Forster says in his book Aspects of the Novel, “critics are more apt to object than readers” to the author being present.

In fact, some of the 19th century’s most popular authors made themselves very present on the page. Just take a look at the opening of Bleak House by Charles Dickens:

London. Michaelmas term lately over, and the Lord Chancellor sitting in Lincoln’s Inn Hall. Implacable November weather. As much mud in the streets as if the waters had but newly retired from the face of the earth, and it would not be wonderful to meet a Megalosaurus, forty feet long or so, waddling like an elephantine lizard up Holborn Hill.

If you haven’t read the full opening of this brilliant book, go take a look at it – it’s such a bold, confident example of “omniscience.” It’s very much Dickens, the author, moving around London, commenting on the state of things.

But despite this freedom, Dickens still limits himself. In the passage above, he swiftly moves from the big-picture view of London into the Court of Chancery and the case of Jarndyce v Jarndyce, which is central to the novel’s plot.

This passage from The Warden by Anthony Trolllope announces the presence of the storyteller even more overtly:

The Rev. Septimus Harding was, a few years since, a beneficed clergyman residing in the cathedral town of ––––; let us call it Barchester. Were we to name Wells or Salisbury, Exeter, Hereford, or Gloucester, it might be presumed that something personal was intended; and as this tale will refer mainly to the cathedral dignitaries of the town in question, we are anxious that no personality may be suspected. Let us presume that Barchester is a quiet town in the West of England, more remarkable for the beauty of its cathedral and the antiquity of its monuments than for any commercial prosperity; that the west end of Barchester is the cathedral close, and that the aristocracy of Barchester are the bishop, dean, and canons, with their respective wives and daughters.

He’s creating the story in front of us, anonymizing the cathedral town and then giving it a fictitious name. A modern author would avoid this. But that’s one of the many joys of reading Trollope: the author is conspicuously present – you’re not just getting the story (the character experience), you’re also spending time with the gregarious author.

Of course Trollope never walks into a scene in the story. He remains as much above or outside the story as Dickens did in the opening to Bleak House.

So, if you want to tell a story using the third-person POV, ask yourself:

How visible or invisible do I want to be?

If invisible, how am I going to keep myself hidden?

How much will I allow myself to “see” or “show” the reader – and how far away or close will I get?

Will I follow one character and limit myself to that person’s thoughts?

Or will I move from one character’s perspective to another – and if so, how will I avoid “head hopping”? Limit one POV per chapter? Or will I shift POV within chapters or even scenes?

Final thoughts

Point of view is a big topic. But try to keep in mind that with a first-person POV story, you are “acting” the part of a character, while with third-person you are telling the story and have to decide how visible or invisible you want to be. Most popular fiction today defaults to invisible authors. But after decades of omniscience being out of fashion, I see it returning gradually in literary fiction – and maybe someday authorial intrusion will become popular again.

Would you welcome a return to more omniscient narration? If you could get authorial intrusion from an author, who would that author be – and why? Leave a comment online.

Thanks for reading – and happy writing!

P.S. Next newsletter, I’ll take a look at POV in Ambrose Bierce’s “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge.” If you want to follow along, feel free to download and read it.